Infinite Quest

By

Jason Cowley

Financial Times, September 14, 2012

Edited by Andy Ross

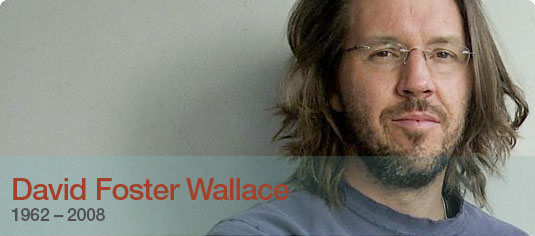

David Foster Wallace felt imprisoned inside his own head. His novel Infinite

Jest (1996) is both funny and sad. It is set in the near future, where

people are searching for the master copy of a film named Infinite Jest. The

secret of the film is that it's so much fun that it paralyzes or kills

anyone who watches it. The novel is over 1,000 pages long and has over 100 pages of footnotes.

Born in 1962, Wallace excelled at sports at

school, but in his teens he started to smoke too much marijuana. In

conversation, he could be tyrannical, overwhelming, eager to show just how

smart he was, the smartest guy in the room. Asked how he knew so much, he

said: "I did the reading." He was addicted to alcohol, marijuana, tobacco,

television, and sex. He wanted to be a great writer.

Wallace

attracted groupies who clustered and swooned at readings. He wrote with the

same curiosity and manic attention about porn, rap, and tennis as he did

about mathematics, philosophy, and literature. He said he felt at times as

if his head would explode. In 2007, he became agitated about what dependency

on prescription drugs was doing to his health. He hanged himself in 2008.

Every Love Story is a Ghost Story

By Benjamin Markovits

The Guardian, September 13, 2012

Edited by Andy Ross

David Foster Wallace is one of those novelists

who seem to push along the evolution of the form. He mixed high and low

references, postmodern philosophy and popular television, mathematical

theory and stoner slang. On his novel Infinite Jest his publisher joked:

"Has anyone here actually read this thing?"

Biographer D.T. Max shows

this is a guy who suffered. Wallace hanged himself in 2008, aged 46, after

years of medicated depression. Max mines Wallace's work for sophisticated

expressions of the author's mental states. The technique not only brings

Wallace to life, it brings the work into play as well.

Wallace grew

up in Urbana, where his father taught philosophy at the University of

Illinois. He went to Amherst, the liberal arts college in Massachusetts, and

graduated top of his class. He fell in love with technical philosophy and

the foundations of mathematics, then moved on to postmodern fiction.

During one period of self-doubt, Wallace signed up for postgraduate work in

philosophy at Harvard, then checked himself into the psychiatric institute

at McLean Hospital. The four weeks he spent there, Max writes, changed his

life: he got clean and spent the rest of his life as a recovering addict.

Not Much Fun

By Ned Beauman

The Guardian, August 30, 2012

David Foster Wallace didn't think an account of his

life would be much fun. He said that "fiction's about how to be a fucking

human being." But the guy telling us this concluded that life wasn't worth

living. His dealings with women were often pretty grimy. He once wondered

aloud to his friend Jonathan Franzen whether his only purpose on earth was

"to put my penis in as many vaginas as possible".

David Foster Wallace

By Thomas Meaney

Times Literary Supplement, March 2013

Edited by Andy Ross

Wallace was regularly proclaimed the voice of his generation. His 1996 novel Infinite Jest and his

stories and essays came just in time. He was fluent in Continental

philosophy and railed against several schools of American fiction. His temperament veered between intellectual one-upmanship and a down-home quality that won him a

devoted following among those willing to overlook how artfully that

unpretentiousness was put together.

Wallace came into his own as a

writer at Amherst College in Massachusetts in the 1980s. As a student he got

top marks, lest anyone mistake him for not being the smartest kid in the

room. But he struggled with depression. In his first published story in the

Amherst Review, Wallace enters the mind of a Brown undergraduate who goes on

anti-depressants after trying to kill himself:

I've been on antidepressants for, what, about a year now, and I suppose I feel as if I'm pretty qualified to tell what they're like. They're fine, really, but they're fine in the same way that, say, living on another planet that was warm and comfortable and had food and fresh water would be fine: it would be fine, but it wouldn't be good old Earth, obviously. I haven't been on Earth now for almost a year, because I wasn't doing very well on Earth.

The narrator sees that depression is a kind of auto-immune deficiency of the self:

All this business about people committing suicide when they're "severely depressed;" we say, "Holy cow, we must do something to stop them from killing themselves!" That's wrong. Because all these people have, you see, by this time already killed themselves, where it really counts. By the time these people swallow entire medicine cabinets or take naps in the garage or whatever, they've already been killing themselves for ever so long. When they "commit suicide," they're just being orderly.

Wallace struggled not only with depression but also with a more ubiquitous

form of cultural malaise. What newspapers were to Kierkegaard, television

was to Wallace. He saw it as an escape into an irony-saturated space where

opinions flow and mutate easily, but where passionate commitments appear

ridiculous. The point was not that television was responsible for turning

America into a nation of addicts. Irony and even cynicism were much needed

for exposing hypocrisy and duplicity.

Infinite Jest is set in the

first decade of the 21st century, in the Organization of North American

Nations (ONAN), a moral wasteland of mass paralysis through entertainment.

The hero discovers that the most enlivening truths are contained in the

deadliest clichés:

The desperate, newly sober White Flaggers are always encouraged to invoke and pay empty lip-service to slogans they don't yet understand or believe — e.g. "Easy Does it!" and "Turn It Over!" and "One Day At a Time!" It's called "Fake It Till You Make It," itself an oft-invoked slogan. Everyone on a Commitment who gets up publicly to speak starts out saying he's an alcoholic, says it whether he believes he is yet or not; then everybody up there says how Grateful he is to be sober today and how great it is to be Active and out on a Commitment with his Group, even if he's not grateful or pleased about it at all. You're encouraged to keep saying stuff like this until you start to believe it, just like if you ask somebody with serious sober time how long you'll have to keep schlepping to all these goddamn meetings he'll smile that infuriating smile and tell you just until you start to want to go to all these goddamn meetings.

Infinite Jest succeeded less in depicting a community of desperate souls

than in creating a community of readers. By the end of the book, Wallace had

barely breached the problem of boredom. So he signed up to take advanced tax

classes and corresponded at length with an IRS veteran about the US tax

code.

The Pale King is at times an excruciating read, not least

because for long stretches Wallace subjects the reader to the boredom about

which he's writing. There is a long scene where Shane Drinion, an IRS

examiner, has a conversation another IRS examiner. In the notes Wallace left

behind for the novel, he says this about Drinion:

Pay close attention to the most tedious thing you can find (tax returns, televised golf), and, in waves, a boredom like you've never known will wash over you and just about kill you. Ride these out, and it's like stepping from black and white into color. Like water after days in the desert. Constant bliss in every atom.

In his Kenyon College Commencement address in 2005, Wallace tells the

students they can choose how to make meaning out of their lives. In the

tides of boredom that wash over us in our daily lives, anyone who harnesses

the power of his own attention is king. We can, as he says, "choose what we

worship".

AR This page could grow into an infinite jest.