Andy Clark, Dave Chalmers |

Wolf Singer All photos: Dave Chalmers |

|

|

| Andy Clark, Rupert Sheldrake |

Christof Koch, Stuart Hameroff |

Tucson 2008

Blogged by John Derbyshire

National Review Online, April 9-13, 2008

Edited by Andy Ross

Wednesday, April 9

We started with a discussion of Benjamin Libet's astonishing results. He

showed that neurophysiologically speaking, your intention to do something

precedes the conscious decision to do it. First, Bill Banks (experimental

psychologist) and Francesca Carota (neuroscientist) presented some

worthy-but-dull quantitative stuff.

John Jacobson (philosopher and

information scientist) described his work at creating an unbeatable

rock-paper-scissors computer program, throwing out all sorts of witty and

penetrating observations on free will, "folk volition" (what we rubes think

volition is all about, as opposed to what it is really all about), and

something called pessimistic indeterminism.

Physicist Daniel Sheehan

(University of California, San Diego) gave us a physicist's account of the

nature of time. Down at the quantum level, things get radically weird, we

all know that. He believes brain processes partake of the weirdness.

Sheehan offered some startling experimental results that seemed to show

presentiment. You show your suspect a blank screen, then you randomly

display a picture, either an "emotional" one, that will evoke a strong

neuro-response (such as a naked woman) or a "calm" one (a seascape). Then

you quickly go back to the blank screen. You are monitoring neural reactions

all the time. The "emotional" pictures produce not only a strong reaction

after they are shown but also a measurably stronger reaction before being

shown.

Sheehan claims he can explain this via known quantum effects,

and says the explanatory power you get by bringing quantum weirdness into

biology makes it worthwhile.

Susan Pockett (University of Auckland,

New Zealand) doubted Libet's famous results, saying he'd made unjustifiable

assumptions. She pooh-poohed Sheehan's quantum weirdness, arguing that there

were less-strange explanations for the phenomena. She scoffed at the

"presentiment" experiment, mocking its statistics.

Andy Clark

(University of Edinburgh) gave an address on the "extended mind." This is

the notion that, as he put it, "skin and skull are porous." He says a

person's mind can fairly be taken to include things other than the brain.

Cute anecdote: "A person asks me, 'Do you know the time?' 'Yes,' I reply

...

and then I look at my watch ... So my 'I' includes my watch."

The

session on "Sex and consciousness" was a let-down. Barry Komisaruk (Rutgers

University) started with an interesting account of some neurophysiological

experiments, then wandered off into the arm-waving zone. Sample: "If time is

a fourth dimension, why can't consciousness be a fifth dimension?"

Jenny Wade told us about some research she'd done. She'd got a sample

heavily loaded with middle-aged university women and asked them about their

mind states during sex.

The evening sessions included a joint lecture

on panpsychism. This seems to have been gaining a lot of ground with the

metaphysicians recently. Very approximately, it's the notion that

consciousness is just the out-cropping or concentration of a "psi field"

that pervades everything. Even electrons and neutrons possess eensy-teensy

little specks of consciousness, according to the panpsychists. Panpsychism

seems, according to its adherents, to offer a glimmer of hope that we might

resolve what they call "the hard problem of consciousness" by describing how

mental events arise out of matter.

Bill Seager (University of

Toronto) had some fun with words and syllogisms. Leopold Stubenberg wanted

to resurrect Russell's "neutral monism" of 80 years ago. Steve Deiss

(University of California, San Diego) stated that "things are

interpretations of qualia." David Skrbina (University of Michigan) gave a

lucid exposition of a dynamical systems theory approach to thinking without

telling us anything about consciousness. Jonathan Powell (University of

Reading) took us back to quantum weirdness, but at the level of neuronal

microtubules.

As part of the session, we were asked to vote on a new

name for panpsychism. We were offered nine choices.

— Panpsychism says either

that all parts of matter involve mind or that the whole universe is an organism that

has a mind.

— Hylozoism

is the idea that all or some material things possess life, or that all life

is inseparable from matter.

— Animism is the belief in souls, which may be

present in animals, plants, and objects, as well as in people.

—

Panexperientialism credits all entities with phenomenal consciousness but

not necessarily with cognition.

— Panprotoexperientialism is weaker and

credits entities only with latent consciousness.

— Quantum animism

attributes spirit, mind, or mentality only to quantum-realm particles.

—

Vitalism invokes a non-physical "élan vital" or spark of life.

—

Neo-psychism is a new term we might coin to circumvent traditional

panpsychism and its connotations.

— Neo-animism is similar.

I voted to

keep "panpsychism."

Thursday, April 10

Thursday was a half day here at the conference. We had four plenary sessions

in the morning, then most of the participants went off on a trip in the

afternoon.

Bernard Baars (San Diego Neuroscience Institute) asked if

consciousness is local or global. Is the faculty of conscious awareness

located at some particular point(s) of the brain, or smeared across the

whole structure? His answer is both. His "global workspace theory" is about

how processing of sensory data can trigger conscious activity, which may

fire off chains of unconscious activity, which may in turn fire back more

conscious processes, and so on. The experimental key is to compare the

conscious with the unconscious processes. Baars brought it nicely together

with some "theater of consciousness" analogies.

Nao Tsuchiya

(California Institute of Technology) described some experiments on monkey

perception. He can deduce what his monkeys are seeing from the firing

patterns of as few as eight individual neurons across 0.1 seconds. I didn't

quite get the connection to reflective consciousness.

Rafael Malach

(neurobiology, Weizmann Institute, Israel) talked about why a particular

neuron responds to certain particular stimuli but not others. He flashed

brief, random video clips on a screen in quick succession with, along the

bottom, a synchronous trace of the activity in one particular neuron

belonging to a subject watching the stream of clips. The neuron was pretty

much idle until a clip of The Simpsons came on, when it went into a rapid

burst of firing. The Simpsons neuron! There was a follow-up of the subject's

voice, in a later interview, being asked to recall as many of the video

clips as she could. Again, not much activity in the neuron till she

mentioned The Simpsons. Neat stuff.

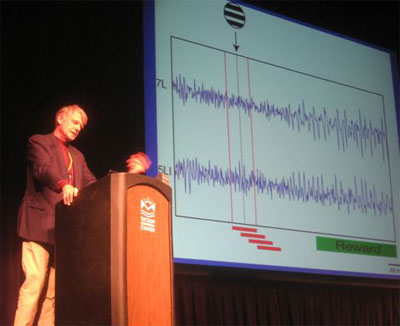

Wolf Singer (Frankfurt Institute

of Advanced Study) gave a long address concentrating on the global aspect of

consciousness and its correlates in the waves of electrical activity that

surge back and forth through the brain when it's conscious. These are really

deep experimental and theoretical waters.

Friday, April 11

The first round of plenary sessions were on "First-Person Methodologies and

the Richness of Consciousness." The first half tackles the question: "How

can we get reliable reports from people about their private mental states?"

The second half translates as: "Just how much are we consciously aware of?"

Are we richly conscious of a lot of things all the time, or

are we only thiny conscious, with most of our mental life composed of vague

impressions and reflections instantly forgotten? This is a historic divide

among writers about consciousness. Eric Schwitzgebel (philosophy, University

of California) argued this one.

Are the contents of

experience poor, in the sense of being only immediate sense impressions,

with second-order judgments about things like causation generated by

upstream neural events, or do we perceive the whole package in a rich way?

Susanna Siegel (philosophy, Harvard University) argued this one. She thinks

there is an "impression of causation," and cited some experimental evidence.

Psychologist Chris Heavey (Univ. Nevada) told us about his methodology. He

gives his subjects beepers that go off at random intervals through the day.

Subjects report exactly what they were conscious of just before the beep.

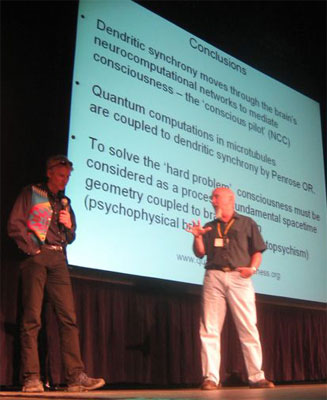

Gestav Bernroider (University of Salzburg) and Stuart Hameroff

(University of Arizona, and the main organizer of this conference) aired

some speculations on quantum neurobiology. Stuart worked up a model of the

brain as a quantum computer, with the tubulin protein molecules of neuron

microtubules as the qubits — "Schrödinger's protein". There's a slight

drawback here, which Stuart phrased as: "The brain is too warm and wet for

delicate quantum-mechanical effects." He suggested some possible

work-arounds.

Stuart wound up with his signature shtick taking in

quantum mechanics, spacetime geometry, Penrose's work, Libet's results

(quantum collapse propagating backwards in time), and a neutral-monist

flavor of panpsychism, consciousness being a process embedded in fundamental

spacetime architecture, "units" of reality collapsing quantumly as either

matter or, in the highly particular circumstances of brain function, as

mind.

Adrian Owen (University of Cambridge, UK) presented some

experimental brain science on what may really be going on in "persistent

vegetative states" (some awareness and speech comprehension, in at least a

few cases). Daniel Langleben talked about using brain scans for lie

detection. Mind reading is just over the horizon, but you'll need an

expensive piece of equipment to do it.

The evening electives

included a session on the evolution of consciousness. At what point in

evolution did consciousness show up? How might we find out? Did it first

show up as late as the Bronze Age? Were Homer's Greeks actually zombies, as

Julian Jaynes suggested? Their self-descriptions of their own mental lives

do seem to be different from ours of ours. Alex Gamma (University of Zürich)

gave some useful reminders about the clumsy, non-optimizing,

non-parsimonious, Rube Goldberg way that evolution actually works. Not every

trait is an adaptation.

Saturday, April 12

Consciousness studies has a problem with its boundaries. If you're trying to

get a science of consciousness going, what do you leave out? There is good

rigorous stuff: brain imaging, neuroscience, experimental psychology, solid

philosophy. But a topic like this is going to attract some New Age types and

the sort of people whose claims get lengthily debunked in Skeptic magazine.

Rupert Sheldrake (biology, Cambridge University, UK) delivered his

address from a chair, having been stabbed in the thigh by a lunatic at a

different consciousness conference earlier in the week. He gave a witty

presentation on dogs, "telephone telepathy," and the awareness some of us

seem to have that we are being stared at from behind, even though we can't

see the starer. Sheldrake has done some experiments, and showed us his

results in summary.

The three following speakers all debunked

Sheldrake to various degrees. Dick Bierman (University of Amsterdam) had

repeated some of Sheldrake's experiments, with deeply unimpressive results.

John Allen (University of Arizona) noted that to explain these odd anecdotal

events by ESP is "conclusion by exclusion," a statistically very weak

procedure. Steven Barker (University of Arizona) demolished Sheldrake's

being-stared-at "results" with Bayesian analysis.

The second session

was on "Psychedelics and Consciousness." Thomas Ray (zoology, University of

Oklahoma) took us deep into neurochemistry. Receptors are protein molecules

on the surface of nerve cells, and a lot of the neurotransmitters that go

with them affect consciousness. Ray claims to have found what he calls a

"meta-receptor," modulating the effect of other receptors. His meta-receptor

turns joy into ecstasy, anger into paranoia, ordinary religious enthusiasm

into the conviction that you are the Messiah. He hasn't published yet.

A New Agey presentation from a practitioner of "transpersonal

psychotherapy" enthused about "a shamanistic psychedelic brew" called

Ayahuasca.

The wind-up session was on the development of

consciousness in babies, infants, and adolescents. These lectures were real

dev-psych research, with brain scans, beepers, questionnaires and all, not

mere philosophical ruminating.

Alison Gopnik (University of

California, Berkeley) lectured on what it's like to be a baby. What it's it

like is a flood of sensations, making it difficult to fix your attention on

any particular thing. Babies are good at exogenous, "bottom up" attention,

but not much good at the endogenous, "top down" variety. The "bottom" here

is raw sensory input; the "top" is the executive self, the "I." Babies don't

have much of an "I." Sample quotes:

"Consciousness narrows as a

function of age."

"As we know more, we see less."

"Babies are designed

to learn, not act. Adults are designed to act, not learn."

Sarah

Akhter (University of Nevada) told us about adolescent consciousness. She'd

done one of those beeper studies to probe the inner lives of adolescents.

Her most alarming results were from an adolescent girl who, from her

self-reporting, seemed to have no inner life at all.

I learned a new

word here: "alexothymia," the inability to describe feelings in words.

Academic conferences are great for your vocabulary. All in all an excellent

conference, with a good broad variety of topics and some great speakers.

AR I wish I had been there, to join in the fun. But the contents would not have surprised me, to judge by this account.