The Red Book

By

Sara Corbett

The New York Times, September 20, 2009

Edited by Andy Ross

Carl Gustav Jung founded the field of analytical psychology. He came to see

the psyche as a spiritual and fluid place, an ocean that could be fished for

enlightenment and healing. Today he is remembered as a countercultural icon,

a proponent of spirituality outside religion and the ultimate champion of

dreamers and seekers everywhere.

Jung was interested in the

psychological aspects of séances, of astrology, of witchcraft. Working at a

Zurich psychiatric hospital, Jung listened intently to the ravings of

schizophrenics. At home, he pored over Dante, Goethe, Swedenborg, and

Nietzsche. He began to study mythology and world cultures. Somewhere along

the way, he started to view the human soul as requiring specific care and

development.

As his convictions began to crystallize, Jung felt his

own psyche starting to teeter and slide. What happened next has been

characterized variously as a creative illness, a descent into the

underworld, a bout with insanity, a narcissistic self-deification, or a

transcendence. Whatever, in 1913, Jung, who was then 38, got lost in the

soup of his own psyche. He was haunted by troubling visions and heard inner

voices.

For about six years, Jung worked to prevent his conscious

mind from blocking out what his unconscious mind wanted to show him.

Whenever there was a spare hour or two, Jung sat in his study and induced

hallucinations. He found himself in a place full of creative abundance and

potential ruin, believing it to be the same borderlands traveled by both

lunatics and great artists.

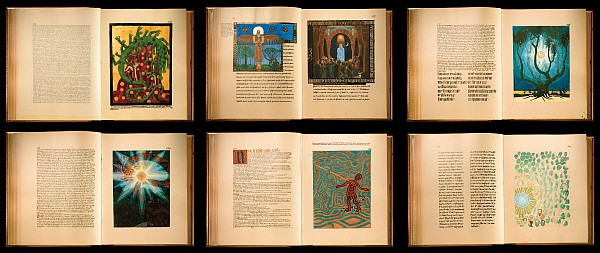

Jung recorded it all. First taking notes

in a series of journals, he then expounded upon and analyzed his fantasies,

writing in a regal, prophetic tone in the big red-leather book. The book

detailed a psychedelic voyage through his own mind. Writing in German, he

filled 205 oversize pages with elaborate calligraphy and with richly hued,

staggeringly detailed paintings.

Jung worked on his red book for

about 16 years, but he never managed to finish it. When he died in 1961, he

left no instructions about what to do with it. In 1984, the family

transferred it to a bank.

Stephen Martin is the director of the

Philemon Foundation, which focuses on preparing the works of Carl Jung for

publication. Martin has raised money to pay for translating the Red Book and

adding an introduction and footnotes written by London-based historian Sonu

Shamdasani.

Shamdasani teaches at the University College London's

Wellcome Trust Center for the History of Medicine. He first approached the

Jung family with a proposal to edit and publish the Red Book in 1997. For

about two years, he flew back and forth to Zurich. Finally, he was granted

permission to proceed in preparing it for publication.

Jung's more

well-known concepts — including his belief that humanity shares a pool of

ancient wisdom that he called the collective unconscious and the thought

that personalities have both male and female components (animus and anima) —

have their roots in the Red Book. Creating the book also led Jung to

reformulate how he worked with clients. A former client recalls Jung's

advice for processing what went on in her mind:

"I should advise you

to put it all down as beautifully as you can — in some beautifully bound

book. It will seem as if you were making the visions banal — but then you

need to do that — then you are freed from the power of them. ... Then when

these things are in some precious book you can go to the book and turn over

the pages and for you it will be your church — your cathedral — the silent

places of your spirit where you will find renewal. If anyone tells you that

it is morbid or neurotic and you listen to them — then you will lose your

soul — for in that book is your soul."

The Red Book is not an easy

journey. It is bombastic, baroque, and like so much else about Carl Jung, a

willful oddity. The text is dense, often poetic, always strange. The art is

arresting and also strange. Even today, its publication feels like an

exposure. For publication, the scanned original is followed by a separate

English translation along with Shamdasani's introduction and footnotes at

the back of the book. It will be in stores in October, published by W. W.

Norton.

Red Therapy

By David Bentley Hart

First Things, December 2012

Edited by Andy Ross

Carl Jung began receiving revelations in 1913, when he was 38 years old. He

undertook to lay open his thoughts in the Red Book, an immense illuminated

manuscript on cream vellum, copiously illustrated with elaborate painted

panels and bound in red leather.

The Red Book is saturated in imagery

and concepts drawn from the Gnostic systems of late antiquity. Its spiritual

logic is one of a saving wisdom vouchsafed through a private revelation. For

Jung, Gnostic myth was a poignantly confused way of talking about the

universal human tragedy. The book preserves the ungainly aspects of ancient

Gnosticism but not its sympathetic religious qualities.

We have

learned to see nature as a machine. The story of evolution appears to

concern only a mindless process of violent attrition and fortuitous

survival. In such a cosmos, many of us imagine transcendence solely as an

absolute absence of God from the world. The deep disquiet of the restless

heart that longs for God becomes a mechanical malfunction in need of

therapy.

Jung quaintly imagined he was working towards some sort of

spiritual renewal for modern man. In fact, he was engaged in the manufacture

of therapeutic sedatives. Gnosticism is reduced to narcissism.

|

|

|