|

|

|

|

The Problem of Evil

By Tony

Judt

New York Review of Books, February 14, 2008

Edited by Andy Ross

Hannah Arendt: "The problem of evil will be the fundamental question of postwar

intellectual life in Europe — as death became the fundamental problem after

the last war."

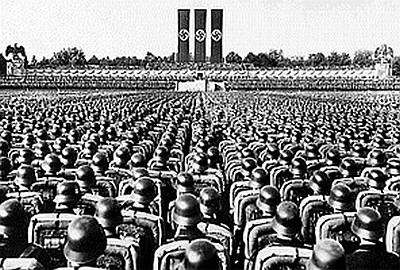

After World War II, the worship of violence largely

disappeared from European life. During this war violence was directed not

just against soldiers but above all against civilians. And the utter

exhaustion of all European nations left few illusions about the glory of

fighting or the honor of death. What did remain was a widespread familiarity

with brutality and crime on an unprecedented scale.

In the aftermath of Hitler's defeat and the Nuremberg trials

lawyers and legislators devoted much attention to the issue of "crimes

against humanity" and the definition of genocide. But while the courts were

defining the monstrous crimes that had just been committed in Europe,

Europeans themselves were doing their best to forget them.

Far from

reflecting upon the problem of evil in the years that followed the end of

World War II, most Europeans turned their heads resolutely away from it. The

Shoah was for many years by no means the fundamental question of postwar

intellectual life in Europe.

In Eastern Europe there were four

reasons:

1 The worst wartime crimes against the Jews were committed there. There was a powerful incentive in many places to forget what had happened, to draw a veil over the worst horrors.

2 Many non-Jewish East Europeans were themselves victims of atrocities and when they remembered the war they thought of their own suffering and losses.

3 Most of Central and Eastern Europe came under Soviet control by 1948. The official Soviet account of World War II was of an anti-fascist war. The millions of dead Jews from the Soviet territories were counted in Soviet losses but their Jewishness was played down or even ignored.

4 After a few years of Communist rule, the memory of German occupation was replaced by that of Soviet oppression.

Everything started to change after the 1960s. By the 1980s the story of

the destruction of the Jews of Europe was becoming increasingly familiar.

Since the 1990s and the end of the division of Europe, official apologies,

national commemoration sites, memorials, and museums have become

commonplace.

Today, the Shoah is a universal reference. The history

of the Final Solution, or Nazism, or World War II is a required course in

high school curriculums everywhere. Hannah Arendt's prophecy would seem to

have come true: the history of the problem of evil has become a fundamental

theme of European intellectual life.

Five difficulties

arise from our contemporary preoccupation with what every schoolchild

now calls the Holocaust:

1 The dilemma of incompatible memories. Western European attention to the memory of the Final Solution is now universal. But the eastern nations that have joined Europe since 1989 retain a very different memory of World War II. Greater attention has been paid to the ordeal of Europe's eastern half at the hands of Germans and Soviets alike.

2 Historical accuracy and the risks of overcompensation. For the first decades after 1945 the gas chambers were confined to the margin of our understanding of Hitler's war. For today's students, World War II is about the Holocaust. In moral terms that is as it should be. But for historians this is misleading. There were only two groups for whom World War II was above all a project to destroy the Jews: the Nazis and the Jews themselves. For practically everyone else the war had quite different meanings.

3 Modern secular society has long been uncomfortable with the concept of evil. We prefer more rationalistic and legal definitions of good and bad, right and wrong, crime and punishment. But in recent years the word has crept slowly back into moral and even political discourse. In recent years politicians, historians, and journalists have used the term "evil" to describe mass murder and genocidal outcomes everywhere. We have lost sight of what it was about twentieth-century political religions of the extreme left and extreme right that was so seductive, so commonplace, so modern, and thus so truly diabolical.

4 We run a risk when we invest all our emotional and moral energies into just one problem. Anti-Semitism, like terrorism, is an old problem. And even a minor outbreak reminds us of the consequences in the past of not taking it seriously enough. But anti-Semitism, like terrorism, is not the only evil in the world.

5 The relationship between the memory of the European Holocaust and the state of Israel has changed. Ever since its birth in 1948, the state of Israel has negotiated a complex relationship to the Shoah. On the one hand the near extermination of Europe's Jews summarized the case for Zionism. Jews could not survive and flourish in non-Jewish lands and they must have a state of their own. On the other hand, Israel's initial identity was built upon treating the Jewish catastrophe as evidence of a weakness that it was Israel's destiny to overcome. But today, when Israel is exposed to international criticism for its mistreatment of Palestinians and its occupation of territory conquered in 1967, its defenders prefer to emphasize the memory of the Holocaust.

The problem of evil in the last

century took the form of a German attempt to exterminate Jews. But it is not

just about Germans and it is not just about Jews. The problem of evil is a

universal problem.

In short, the Holocaust may lose its universal

resonance. We need to find a way to preserve the core lesson that the Shoah

really can teach: the ease with which a whole people can be defamed,

dehumanized, and destroyed. But we shall get nowhere unless we recognize

that this lesson could indeed be questioned, or forgotten.

There is more than one sort of banality. There is the notorious banality of which

Arendt spoke — the everyday evil in humans. But there is also the banality

of overuse — the numbing effect of seeing or saying or thinking the same

thing too many times.

The problem of evil remains the fundamental

question for intellectual life.

Germany Confronts Holocaust

By Nicolas Kulish

New York Times, January 29, 2008

Edited by Andy Ross

Most countries celebrate the best in their pasts. Germany unrelentingly

promotes its worst.

The enormous Holocaust memorial that

dominates a chunk of central Berlin was completed only after years of

debate. But the building of monuments to the Nazi disgrace continues

unabated.

On Monday, Germany's minister of culture, Bernd

Neumann, announced that construction could begin in Berlin on two

monuments: one near the Reichstag, to the murdered Gypsies, known here

as the Sinti and the Roma; and another not far from the Brandenburg

Gate, to gays and lesbians killed in the Holocaust.

In November

Germany broke ground on the long-delayed Topography of Terror center at

the site of the former Gestapo and SS headquarters. And in October, a

huge new exhibition opened at the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. At

the Dachau camp, outside Munich, a new visitor center is set to open

this summer. The city of Erfurt is planning a museum dedicated to the

crematoriums. There are currently two exhibitions about the role of the

German railways in delivering millions to their deaths.

Wednesday

is the 75th anniversary of the day Hitler and the Nazi Party took power

in Germany, and the occasion has prompted a new round of soul-searching.

"Where in the world has one ever seen a nation that erects memorials

to immortalize its own shame?" asked Avi Primor, the former Israeli

ambassador to Germany, at an event in Erfurt on Friday commemorating the

Holocaust and the liberation of Auschwitz. "Only the Germans had the

bravery and the humility."

The Banality of Intellect

By Jan Mieszkowski

LA Review of Books, July 2013

The study of Nazi Germany and the Holocaust is still haunted by

questions about what kind of people could perpetrate such unspeakable

crimes. Hannah Arendt

observed that the heads of the SS death squads that conducted mass

killings on the Eastern front were members of an intellectual elite.

Christian Ingrao and others have concentrated on the SD, the

intelligence arm of the SS. The SD was an extremely professional

organization that attracted ambitious, highly educated young men and

became a real academic force before serving as the vanguard of genocide.

Ingrao finds that the dissertations of

these young scholars betray a subtle politicization of research that

began with the erosion of the boundary between intellectual inquiry and

activism. With a broad mandate for surveillance and investigation,

members of the SD followed the methodological dictates of the academic

social sciences in which they had been trained to develop a dynamic

account of German cultural and economic life.

Operation

Barbarossa and the Nazi invasion of Soviet territory saw a radical

transformation of the agenda as the officers were sent to lead death

squads on the Eastern Front. Participating in the drive east was

ostensibly an opportunity to implement Nazi plans for the restructuring

of lands and peoples on an unprecedented scale. The SD made an effort to

explain how the SS operations were part of a plan.

Ingrao treats

violence as a system of performances and representations not reducible

to the emotions or intentions of an individual or group of individuals.

His aim is to show that the executions were codified rituals with

carefully crafted gestures and procedures, all designed to lend the

slaughter a veneer of inevitability while defusing the taboos associated

with firing on unarmed women and children.

AR The problem is a good one — worth the time of a serious philosopher.

|

|

|