How dare you call me a fundamentalist

Extracted from:

The God Delusion

By Richard Dawkins

Edited by Andy Ross

I wish to dissociate myself from your shrill, strident, intemperate,

intolerant, ranting language.

Objectively judged, the language

of The God Delusion is less shrill than we regularly hear from political

commentators or from theatre, art, book or restaurant critics. The illusion

of intemperance flows from the unspoken convention that faith is uniquely

privileged.

You can't criticise religion without detailed study

of learned books on theology.

I need engage only those few

theologians who at least acknowledge the question, rather than blithely

assuming God as a premise. Most Christians happily disavow Baal and the

Flying Spaghetti Monster without reference to monographs of Baalian exegesis

or Pastafarian theology.

You attack crude, rabble-rousing

chancers rather than facing up to sophisticated theologians.

If

subtle, nuanced religion predominated, the world would be a better place and

I would have written a different book. The melancholy truth is that decent,

understated religion is numerically negligible.

You're preaching

to the choir. What's the point?

The nonbelieving choir is much

bigger than people think, and it desperately needs encouragement to come

out. Judging by the thanks that showered my North American book tour, my

articulation of hitherto closeted thoughts is heard as a kind of liberation.

You're as much a fundamentalist as those you criticise.

No, please, do not mistake passion, which can change its mind, for

fundamentalism, which never will.

I'm an atheist, but people need

religion.

What patronising condescension! I believe that, given

proper encouragement to think, and given the best information available,

people will courageously cast aside celestial comfort blankets and lead

intellectually fulfilled, emotionally liberated lives.

True faith is greater than the ranters

William Rees-Mogg replies to

Professor Richard Dawkins

The Times, May 14, 2007

Edited by Andy Ross

I agree with Professor Dawkins, not to mention St Paul, in rejecting the

argument that people should be allowed their religious comfort, even if it

is not true.

However, there is one charge against Professor Dawkins

on which his defence merely confirms his critics. It is said that he “often

ignores the best of religion” and instead attacks what are called “crude

rabble-rousing chancers” rather than facing up to sophisticated theologians.

Professor Dawkins’s reply makes a significant concession to his

critics. He does not claim to have answered the argument for belief in God

at its best. He maintains that “the melancholy truth is that decent,

understated, religion is numerically negligible”, but that the world needs

to face the fundamentalists.

He makes an assertion that the vast

majority of religious believers are closer to the beliefs of American

evangelists or of bloodthirsty Islamic terrorists than to quiet and rational

religion. I believe it to be false. It is certainly false in England.

However, I object to Professor Dawkins’s methods of argument much more

than to his assertions of fact, mistaken though I think them to be. Dawkins

is a scientist, and a good one. He has been thoroughly trained in the

scientific method. That requires him to examine conflicting theories in

terms of their strongest arguments, not in terms of their weakest.

His tone is not like that of Charles Darwin himself; thoughtful, reflecting

detailed observation, sensitive in the search for truth. It is more like

that of Bishop Wilberforce in the Oxford debate of June 1860, in which the

bishop attacked Darwinism.

Darwin's Angel

By Salley Vickers

The Times, September 1, 2007

Edited by Andy Ross

Darwin's Angel

An Angelic Response to the God Delusion

By John

Cornwell

This book is a piece of sheer heaven. It is deliciously wise, witty and

intellectually sharp.

John Cornwell’s mouthpiece is a likeable

seraph. Cornwell clearly believes that angels are archetypal images that

dramatise the invisible realities. As such, they can act as symbols for the

formless elements of physics; but also for the creative imagination.

The seraph begins by politely nailing Dawkins’s first sleight of hand

which bundles all religious belief and practice into one crude bag that

supposedly equals fanaticism.

This is rather like suggesting that

all science is dangerous because it has brought nuclear weapons; or that all

education is mistaken because children have been whipped by so-called

educators.

It is child’s play to denounce a subject by pointing to

the myriad ways in which it may be misapplied. But it is faulty logic to

conclude that this is necessarily the fault of the set of ideas being

traduced.

Next the seraph gently takes Dawkins to task for his breezy

disregard for serious theology. You cannot criticise a theory until you have

made some proper attempt to come to grips with it.

His account of

the Bible is equally undiscriminating. For a start, even the first readers

of Genesis would have distinguished between the fact of fact and the fact of

fiction, a distinction that escapes Dawkins.

Nor is the Bible “a

book” but, as the affable seraph points out, a miscellany of stories,

letters, polemic, histories, fables and certainly some great moral

teachings.

Therefore, it is perfectly respectable to “pick and

choose” when reading the Bible, something that Dawkins takes Christians to

task for. For the ancients, a history would be a mixture of reportage,

received wisdom, narrative and story.

The life of Jesus is told in a

series of stories to convey the essence of a life that was demonstrably an

influential one and continues to be so. Just as Jesus told stories to get

across his points, the Gospellers told stories about him.

But what is

most worrying in the Dawkins ideology, as the gracefully admonishing seraph

points out, is the violently biased language in a book that claims to reveal

the deleterious effects of bias. Dawkins uses the image of a virus and

employs a Darwinian model to explain how cultural ideas spread.

If

only Professor Dawkins would remember that Socrates was deemed the wisest of

men because he “knew that he didn’t know”. Those who think that not knowing

is safer and more attractive than its opposite should treat themselves to

this elegant little book.

The Truth in Religion

By John Polkinghorne

Times Literary Supplement, October 31, 2007

Darwin's Angel

An Angelic Riposte to The God Delusion

By John

Cornwell

In God We Doubt

Confessions of a Failed Atheist

By John Humphrys

Religious belief is currently under heavy fire. The two books under review

aim to make a more temperate contribution to the debate.

John

Cornwell has hit on the amusing conceit of writing in the persona of Richard

Dawkins’s guardian angel. The book’s tone is gently ironic and its style

that of modest discussion. Cornwell points out that Dawkins makes no serious

attempt to engage with the academic discussion of religious thought and

practice. Theologians have wrestled with how human language can attempt to

speak about the nature of God, emphatically rejecting the idea that the

deity is simply an invisible object among the other objects of the world.

John Humphrys is respectful of religious belief. His approach is that of

one who remains open and questioning. Humphrys takes very seriously the

human experience of conscience, urging us to do some things and to refuse to

do others. Evolutionary thinking offers us some partial understanding of

this, with its concepts of kin altruism and reciprocal altruism. Humphrys

sees ethical intuition as the signal of a transcendent dimension in life,

which he values but does not know how to explain from an atheist point of

view.

Both Dawkins and Humphrys rightly engage with the challenge to

theism that is represented by the existence of a world claimed to be the

creation of a good and powerful God, but which nevertheless contains so much

evil and suffering. Science shows that natural processes are inextricably

entangled with each other. The integrity of creation is a kind of package

deal. Only a world with sufficient reliability for deeds to have foreseeable

consequences could be one in which moral responsibility was exercised.

Fundamental to the discussion is the relationship between faith and

reason. Religious faith is not a matter of the unquestioning acceptance of

unmotivated belief. Faith is a commitment to a form of motivated belief,

differing only from scientific reason in the nature of the subject of that

belief and the kind of motivations appropriate to it. Science achieves its

success by the modesty of its ambition, only considering impersonal

experience open to repetition at will. The concept of reality offered by

scientism is that of a world of metastable, replicating and

information-processing systems, but it has no persons in it.

No

progress will be made in the debate about religious belief unless

participants are prepared to recognize that the issue of truth is as

important to religion as it is to science.

AR (2007) I like the idea of angels as symbols

of the formless elements of physics, somewhere in the mathematical murk of

the stringscape. Angels as avatars of our own souls, conceived as loopy

swirls in a hyperspace beyond our present scientific imagination, fly way

above the Darwinian jungle or the primordial soup of the macromolecular gene

pool.

Happy Newton Day!

By

Richard Dawkins

New Statesman, December 13, 2007

December 25th is a date to celebrate not because it is the disputed birthday

of the "son of God" but because it is the actual birthday of one of the

world's greatest men.

A charismatic wandering preacher called Jesus

probably was executed during the Roman occupation, but nobody takes

seriously the legend that he was born in December. Late Christian tradition

simply attached Jesus's birth to a long-established and convenient winter

solstice festival.

December 25th is the birthday of one of the truly

great men ever to walk the earth, Sir Isaac Newton. His achievements might

justly be celebrated from one end of the universe to the other.

AR This is such a poor joke, it's not even worth

a smiley.

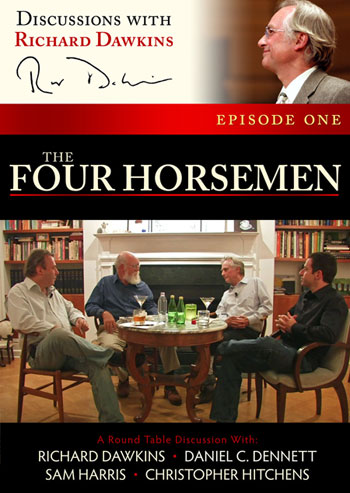

On September 30, 2007, Richard Dawkins, Daniel Dennett, Sam Harris, and

Christopher Hitchens sat down for a first-of-its-kind, unmoderated 2-hour

discussion, convened by RDFRS and filmed by Josh Timonen. All four authors

have received a large amount of media attention for their writings against

religion. In this conversation the group trades stories of the public's

reaction to their recent books, their unexpected successes, criticisms and

common misrepresentations. They discuss the tough questions about religion

that face the world today, and propose new strategies for going forward.

Richard Dawkins and His Selfish Meme

By Pat Shipman

New York Sun, April 23, 2008

Edited by Andy Ross

Proclaimed brilliant for its portrayal of the "gene's-eye view" of

evolution, Dawkins's book inverted the focus of natural selection, from

Darwin's weight on species to Dawkins's emphasis on the gene itself.

Dawkins argued that the crux of natural selection is whether a

particular gene — not an individual or a group of individuals — replicates

itself in future generations. Those genes that are not replicated into the

future have failed at evolution, and those that produce many copies of

themselves have succeeded.

In Dawkins's view, the organisms

containing those genes are merely "lumbering robots" or "survival machines"

that house and carry genetic information. The implication is that

selfishness pays off, and altruism does not.

Some predicted that this

book would be the death knell of the idea of group selection. Has the book

in fact killed off group selection ideas?

Group selection and kin

selection are not dead. In 2007, David Sloan Wilson, professor at

Binghampton University, and E.O. Wilson (no relation), a professor emeritus

at Harvard University and a Pulitzer Prize winner, proclaimed that Dawkins

had celebrated the death of group selection prematurely.

The pair

asserted persuasively that altruism and cooperation can be adaptive if they

are directed toward relatives who share a suite of one's genes (kin

selection) or if relationships can be established within a group in which

cooperation is rewarded with future reciprocity.

Further, when

competition between groups is more significant than that within a group,

natural selection can operate on multiple levels, from gene to kin group to

species and perhaps beyond. The evolutionary disadvantage to the individual

must be weighed against the evolutionary advantage to its larger group (kin,

population, or even species). Since altruistic behaviors do occur, evolution

must operate at both the higher (between-group) as well as the lower

(within-group) level.

This multilevel view of evolution accords well

with a concept espoused by the late John Maynard Smith, formerly an emeritus

professor of the University of Sussex, and Eörs Szathmáry, professor at

Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest. The pair suggested that evolutionary

history is marked by major transitions that correspond to successively more

complex levels of organization.

A favorite example of such a

transition is the development of eusociality, the most extreme instance of

group selection, on which E.O. Wilson is one of the world's experts.

Eusocial species (termites, ants, wasps, naked mole rats, and others) live

in large colonies in which many individuals forego reproduction to assist a

single queen. Wilson's classic 1975 book Sociobiology attributed eusociality

to the close genetic relationship along the colony members.

Wilson

now suggests that eusocial behavior evolves in rare species that have the

flexibility to be reproductive or not, and that live in circumstances

inhibiting the dispersal of nests. Once forced to live together rather than

founding new colonies, species preadapted to cooperation successfully adopt

eusociality precisely because it is evolutionarily advantageous.

A

quip sometimes called Orgel's Second Rule is "Evolution is cleverer than you

are." Evolution is apparently cleverer than Richard Dawkins, because kin and

group selection do exist — and pay off. However, an essential aspect of

being a scientist is to test your theories against new data, and Dawkins's

selfish-gene concept spurred a great deal of hard thought and data

collection that have been used to test his hypothesis.

Because his

works are so lucid and so stunning, Dawkins's ideas have assumed a life of

their own. His powerful metaphor of the inherent selfishness of the gene was

misunderstood by many and often taken deeply to heart. The picture of

evolution offered by Dawkins, which many found bleak, also contributed to

the growth and stridency of the intelligent design movement to undercut the

teaching of evolution in public schools.

Unfortunately, his warnings

against taking moral and ethical lessons from scientific findings were not

universally heeded. The benefit to science of his selfish gene meme in

triggering a new understanding of the magnificent complexity of evolutionary

processes must be weighed against the harm the book has done.

AR (2008) Multilevel group selection sounds convincing to me. Among such groups in Homo sapiens are the fertility cults associated with the Abrahamic God (the god of our fathers — Goof). All life is genocentric — Dawkins. Human life celebrates its genocentricity in fertility cults that drive their followers to go forth and multiply. Such behavior is inexplicable from the standpoint of the rational individualist. A proof that humans are genocentric is their devotion to goofy cults. This deserves a slogan — Goof is great and Dawkins is his prophet!