|

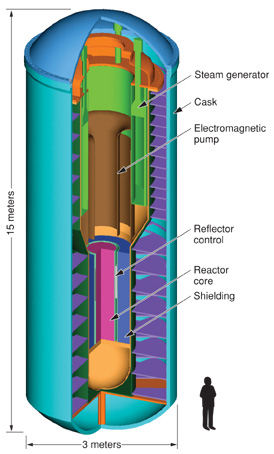

Lawrence Livermore concept for a self-contained thorium reactor. |

Intellectual Ventures

By Malcolm Gladwell

The New Yorker, May 12, 2008

Edited by Andy Ross

In

1999, when Nathan Myhrvold left Microsoft and struck out

on his own, he set himself an unusual goal. He wanted to see whether the

kind of insight that leads to invention could be engineered. He formed a

company called Intellectual Ventures. He wanted to make insights — to come

up with ideas, patent them, and then license them to interested companies.

One rainy day last November in a conference room in the Intellectual

Ventures laboratory, Myhrvold held an invention session on the technology of self-assembly. What if it was

possible to break a complex piece of machinery into a thousand pieces and

then have the machine put itself back together again? That had to be useful.

But for what?

Chairing the meeting was Casey Tegreene, the chief patent counsel for

IV. He stood at one end of the table. Myhrvold was at the opposite end.

Next to him was Edward Jung, whom Myhrvold met at Microsoft. On the other side of the

table from Jung was Lowell Wood.

Myhrvold and Wood have known each other since Myhrvold was a

teenager and Wood interviewed him for a graduate fellowship called the

Hertz. Wood bent the rules for Myhrvold. The Hertz was supposed to be for

research in real-world problems, but Myhrvold's field at that point was

quantum cosmology.

The chairman of the chemistry department at

Stanford, Richard Zare, had flown in for the day, as had Eric Leuthardt, a

young neurosurgeon from Washington University. At the back was Rod

Hyde.

Tegreene started. He and his staff had reviewed the relevant

scientific literature and recent patent filings in order to come up with a

short briefing on what was and wasn't known about self-assembly.

Before long,

the talk swung to how to improve X-rays, and then to the

puzzling phenomenon of soldiers in Iraq who survive a bomb blast only to die

a few days later of a stroke. Wood thought it was a shock wave, penetrating

the soldiers' helmets and surging through their brains, tearing blood

vessels away from tissue. "Lowell is the living example of something better

than the Internet," Jung said after the meeting was over. "On the Internet,

you can search for whatever you want, but you have to know the right terms.

With Lowell, you just give him a concept, and this stuff pops out."

Intellectual Ventures held its first invention session in 2003. "Afterward, Nathan kept saying,

'There are so many inventions,'

" Wood recalled. "He thought if we came up with a half-dozen good ideas it

would be great, and we came up with somewhere between fifty and a hundred. I

said to him, 'But you had eight people in that room who are seasoned

inventors. Weren't you expecting a multiplier effect?' And he said,

'Yeah,

but it was more than multiplicity.' Not even Nathan had any idea of what it

was going to be like."

The original expectation was that IV would

file a hundred patents a year. Currently, it's filing five hundred a year.

It has a backlog of three thousand ideas. Wood said that he once attended a

two-day invention session presided over by Jung, and after the first day the

group went out to dinner. "So Edward took his people out, plus me," Wood

said. "And the eight of us sat down at a table and the attorney said, ‘Do

you mind if I record the evening?' And we all said no, of course not. We sat

there. It was a long dinner. I thought we were lightly chewing the rag. But

the next day the attorney comes up with eight single-spaced pages flagging

36 different inventions from dinner."

Bill Gates: "I can give

you fifty examples of ideas they've had where, if you take just one of them,

you'd have a startup company right there." Gates has participated in a

number of invention sessions, and, with other members of the Gates

Foundation, meets every few months with Myhrvold to brainstorm about things.

One of the sessions that Gates participated in was on the possibility of

resuscitating nuclear energy. "Teller had this idea way back when that you

could make a very safe, passive nuclear reactor," Myhrvold explained. "No

moving parts. Proliferation-resistant. Dead simple. Every serious nuclear

accident involves operator error, so you want to eliminate the operator

altogether. Lowell and Rod and others wrote a paper on it once. So we did

several sessions on it."

The plant, as they conceived it, would

produce one to three gigawatts of power. The reactor core would be enclosed

in a sealed, armored box. The box would work for thirty years, without need

for refuelling. Wood's idea was that the box would run on thorium, which is

a very common, mildly radioactive metal. Myhrvold's idea was that it should

run on spent fuel from existing power plants. "Waste has negative cost,"

Myhrvold said. "This is how we make this idea politically and regulatorily

attractive. Lowell and I had a monthlong no-holds-barred nuclear-physics

battle. He didn't believe waste would work. It turns out it does." Myhrvold

grinned. "He concedes it now."

It was a long-shot idea, easily

15 years from reality, if it became a reality at all. It was just a

tantalizing idea at this point, but who wasn't interested in seeing where it

would lead? "We have thirty guys working on it," he went on. "I have more

people doing cutting-edge nuclear work than General Electric. We're looking

for someone to partner with us, because this is a huge undertaking."

Last March, Myhrvold decided to do an invention session with Eric Leuthardt

and several other physicians in St. Louis. Rod Hyde came, along with a

scientist from MIT named Ed Boyden. Wood was there as well.

"Lowell came in looking like the Cheshire Cat," Myhrvold recalled. "He said,

'I have a question for everyone. You have a tumor, and the tumor becomes

metastatic, and it sheds metastatic cancer cells. How long do those

circulate in the bloodstream before they land?' And we all said, 'We don't

know. Ten times?' 'No,' he said. 'As many as a million times.' Isn't that

amazing? If you had no time, you'd be screwed. But it turns out that these

cells are in your blood for as long as a year before they land somewhere.

What that says is that you've got a chance to intercept them."

Wood: "It turns out that some small per

cent of tumor cells are actually the deadly ones. Tumor stem

cells are what really initiate metastases. And isn't it astonishing that

they have to turn over at least ten thousand times before they can find a

happy home? You naïvely think it's once or twice or three times. Maybe five

times at most. It isn't. In other words, metastatic cancer — the brand of

cancer that kills us — is an amazingly hard thing to initiate. Which

strongly suggests that if you tip things just a little bit you essentially

turn off the process."

The discussion raced ahead. Myhrvold and his

inventors had already done a lot of thinking about using tiny optical

filters capable of identifying and zapping microscopic particles. They also

knew that finding cancer cells in blood is not hard. They're often the wrong

size or the wrong shape. So what if you slid a tiny filter into a blood

vessel of a cancer patient? "You don't have to intercept very much of the

blood for it to work," Wood went on. "Maybe one ten-thousandth of it. The

filter could be put in a little tiny vein in the back of the hand, because

that's all you need. Or maybe I intercept all of the blood, but then it

doesn't have to be a particularly efficient filter."

Wood was a

physicist, not a doctor, but that wasn't necessarily a liability, at this

stage. "People in biology and medicine don't do arithmetic," he said. He

wasn't being critical of biologists and physicians: this was, after all, a

man who read medical journals for fun. Wood had the advantages of someone looking at a familiar

fact with a fresh perspective.

Surgeons had all

kinds of problems that they didn't realize had solutions, and physicists had

all kinds of solutions to things that they didn't realize were problems. At

one point, Myhrvold asked the surgeons what, in a perfect world, would make

their lives easier, and they said that they wanted an X-ray that went only

skin deep. They wanted to know, before they made their first incision, what

was just below the surface. When the Intellectual Ventures crew heard that,

their response was amazement. "That's your dream? A subcutaneous X-ray? We

can do that."

Insight could be orchestrated: that was the

lesson.

Nathan Myhrvold is

the founder and CEO of Intellectual Ventures. During his 14-year tenure at

Microsoft, he was responsible for founding Microsoft Research and numerous

technology groups that resulted in many of Microsoft's most successful

products. Earlier, he was a postdoctoral fellow at Cambridge University and

worked with Stephen Hawking on research in cosmology, quantum field theory

in curved space time and quantum theories of gravitation. Myhrvold earned a

doctorate in theoretical and mathematical physics and a master's degree in

mathematical economics from Princeton University.

|

|

|