Marxism Today

By Stuart Jeffries

The Guardian July 4,

2012

Edited by Andy Ross

In the second best-selling book of all time, The Communist Manifesto, Marx

and Engels wrote: "What the bourgeoisie therefore produces, above all, are

its own grave-diggers. Its fall and the victory of the proletariat are

equally inevitable."

Today the proletariat, far from burying

capitalism, are keeping it on life support. Overworked, underpaid workers in

China keep those in the west playing with their iPads. Chinese money

bankrolls an otherwise bankrupt America.

Jacques Rancière: "The

domination of capitalism globally depends today on the existence of a

Chinese Communist party that gives delocalized capitalist enterprises cheap

labour to lower prices and deprive workers of the rights of

self-organization. … The disappearance of our factories, that's to say

de-industrialization of our countries and the outsourcing of industrial work

to the countries where labour is less expensive and more docile, what else

is this other than an act in the class struggle by the ruling bourgeoisie?"

Slavoj Žižek says the fundamental class antagonism is between use value

and exchange value. Under capitalism exchange value becomes autonomous: "It

is transformed into a specter of self-propelling capital which uses the

productive capacities and needs of actual people only as its temporary

disposable embodiment. Marx derived his notion of economic crisis from this

very gap: a crisis occurs when reality catches up with the illusory

self-generating mirage of money begetting more money – this speculative

madness cannot go on indefinitely, it has to explode in even more serious

crises. The ultimate root of the crisis for Marx is the gap between use and

exchange value: the logic of exchange-value follows its own path, its own

mad dance, irrespective of the real needs of real people."

Marx and

Engels: "Let the ruling classes tremble at a communist revolution. The

proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains. They have a world to

win."

By John Gray

The New York Review of Books, May 9, 2013

Edited by Andy Ross

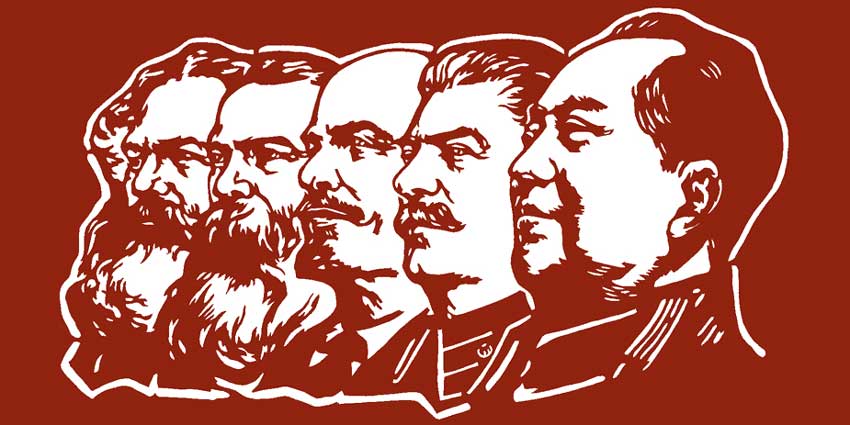

Karl Marx was a nineteenth-century thinker engaged with the ideas and events

of his time. He understood crucial features of the capitalism of the

19th century, but not of the capitalism that exists in the

21st century. He looked ahead to a new kind of human society that

would come into being after capitalism had collapsed, but he had no settled

conception of what such a society would be like.

Today Marx is

inseparable from the idea of communism, but he was not always wedded to it.

In 1842, in his first newspaper editorial, Marx launched a polemic against a

newspaper for publishing articles advocating communism. He declared that the

spread of communist ideas would "defeat our intelligence, conquer our

sentiments," and any attempt to realize communism could easily be cut short

by force of arms. In 1848, Marx rejected revolutionary dictatorship by a

single class as "nonsense", and over twenty years later he dismissed any

notion of a Paris commune as nonsense.

Despite all his efforts, Marx

never formed a unified system of ideas. One reason for this was the

disjointed character of his working life. Though we think of Marx as a

theorist ensconced in the library of the British Museum, theorizing was only

one of his avocations, and he borrowed ideas from many sources.

Positivism produced an enormously influential body of ideas. Originating

with Henri de Saint-Simon and Auguste Comte, positivism promoted a vision of

the future that remains pervasive and powerful today. Asserting that science

was the model for any kind of genuine knowledge, Comte looked forward to a

time when traditional religions had disappeared, the social classes of the

past had been superseded, and industrialism reorganized on a rational and

harmonious basis.

Marx's account of human development was similar to

that of Herbert Spencer, who invented the expression "survival of the

fittest" and used it to defend Victorian capitalism. Influenced by Comte,

Spencer divided human societies into two types, the militant and the

industrial, where the former included all past forms and the latter marked a

new age of science in history. The graves of Marx and Spencer stand face to

face in Highgate Cemetery in London.

Marx derived his view of history

as an evolutionary process culminating in a scientific civilization from the

positivists. He also absorbed something of their theories of racial types.

Marx: "This combination of Jewry and Germanism with the negroid basic

substance must bring forth a peculiar product. The pushiness of this lad is

also nigger-like." In 1866, Marx praised Trémaux's theory of evolution as being "much more important and much richer than Darwin"

for showing that "the common Negro type is only the degenerate form of a

much higher one".

Marx's admiration for Darwin is well known. He

welcomed the theory of evolution as another intellectual blow struck in

favor of materialism and atheism. Followers of Darwin at the time believed

he had given a scientific demonstration of progress in nature, but his

theory of natural selection says nothing about betterment. Marx understood

this absence of the idea of progress in Darwinism. Yet he was just as

emotionally incapable as they were of accepting the contingent world that

Darwin had uncovered.

Marx was a German philosopher. His

interpretation of history derived not from science but from Hegel's

metaphysical account of the unfolding of Geist in the world. Marx famously

turned Hegel's philosophy on its head: In the course of this reversal

Hegel's belief that history is a process of rational evolution

reappeared as Marx's conception of a succession of progressive revolutionary

transformations. The full development of human

powers was for Marx the end point of history. What Marx and many

others wanted from the theory of evolution was an underpinning for their

belief in progress toward a better world. Refusing to accept Darwin's

discovery, Marx turned instead to Trémaux's theories.

Marx believed

that a different and better world could come into being once capitalism had

been destroyed. His ideas were partly responsible for the crimes of

communism. The Soviet Union was a result of attempting to realize a Marxist

vision. The deadly mix of metaphysical certainty and pseudoscience that

Lenin imbibed from Marx created a repressive and inhuman totalitarianism.

In the Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels declared: "All that is solid

melts into air, all that is holy is profaned and man is at last compelled to

face, with sober senses, his real conditions of life, and his relations with

his kind."

Free market conservatives assume that the impact of the

market can be confined to the economy. Marx showed that this is mistaken.

Although nationalism and religion have not faded away, he perceived how

capitalism was undermining bourgeois life. He grasped a vital truth.

|

|

|