Image

origin unknown

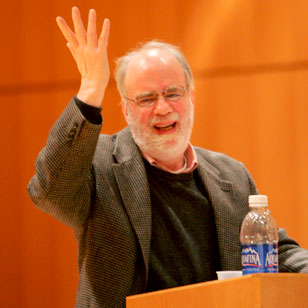

Saul Kripke

Saul Kripke turned 65

By

Charles McGrath

The New York Times, January 28, 2006

Edited by Andy Ross

Saul Kripke turned 65 on November 13, 2005.

In January 2006, the

philosophy program at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York

convened a two-day conference celebrating his birthday and work.

He gave a lecture called "The First Person."

In 2001, Kripke was

awarded the Schock Prize, philosophy's equivalent of the Nobel. He is

thought to be the world's greatest living philosopher, perhaps the greatest

since Wittgenstein. Unlike Wittgenstein, who was small, slender and

hawklike, Kripke looks the way a philosopher ought to look: pink-faced,

white-bearded, rumpled, squinty. He carries his books and papers in a

plastic shopping bag.

A rabbi's son, Saul Aaron Kripke was born in

New York and grew up in Omaha. By all accounts he was a true prodigy. In the

fourth grade he discovered algebra, and by the end of grammar school he had

mastered geometry and calculus and taken up philosophy. While still a

teenager he wrote a series of papers that eventually transformed the study

of modal logic. One of them, or so the legend goes, earned a letter from the

math department at Harvard, which hoped he would apply for a job until he

wrote back and declined, explaining, "My mother said that I should finish

high school and go to college first."

The college he eventually chose

was Harvard. "I wish I could have skipped college," Kripke said in an

interview. "I got to know some interesting people, but I can't say I learned

anything. I probably would have learned it all anyway, just reading on my

own."

While still a Harvard undergrad, Kripke started teaching

post-graduates down the street at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology,

and after getting his B.A. didn't bother to acquire an advanced degree. Who

could teach him anything he didn't already know? Instead, he began teaching

and publishing. His 1980 book

Naming and Necessity is among the most influential philosophy books of

the last 50 years, and his 1982

book on

Wittgenstein's philosophy is so self-assured that some scholars now

refer to a sort of composite figure known as Kripkenstein.

"Before

Kripke, there was a sort of drift in analytic philosophy in the direction of

linguistic idealism — the idea that language is not tuned to the world,"

Richard Rorty, an emeritus professor of comparative literature at Stanford,

said recently. "Saul almost single-handedly changed that."

Except on

very rare occasions, Kripke does not actually set words down on paper. He

broods, gathers a few texts, makes a loose mental outline, and then at some

public occasion, a lecture or a seminar, he just wings it, talks off the top

of his head. These talks are later transcribed and Kripke edits and revises

them, draft after draft, before approving them for publication.

Michael Devitt, a CUNY professor and former head of the philosophy program

at the Graduate Center who was instrumental in bringing Kripke there, said

of the Kripkean method: "He just seems to work it all out in his head. It's

as if he's got privileged access to reality."

Kripke's talk, "The

First Person," dealt with the philosophical question of the meaning and

reference of the pronoun "I" and got into some heady metaphysical

speculation about the nature of the self. Speaking in a squeaky,

high-pitched voice, he circled round and round his subject, riffing on other

philosophers and occasionally darting off for a digression on, say, obesity

or the theory of intelligent design. When he finished, he got a standing

ovation.

Afterward, Kripke graciously endured a small onslaught of

groupies. A graduate student from Rutgers, Karen Lewis, explained that it

was her birthday too, and that the photo session was her present to herself.

"You're my favorite 20th-century philosopher," she said. "I'm so excited!"

Kripke beamed in a way that suggested an authentic inner state of

happiness.

Saul Kripke, Genius Logician

By Andreas

Saugstad

February 25, 2001

Edited by Andy Ross

Saul Kripke is one of the greatest thinkers in modern philosophy. When he

visited Oslo to give a lecture at my university, I met him at a local

restaurant to do an interview.

Kripke has give many original

contributions to philosophy, and many doctoral dissertations have been

written on his work. But Kripke has also been criticized. A former student

wrote a novel where the main character seems to be modeled after Kripke. In

this novel,

The Mind-Body Problem, the main character has a problem with the

relation between the abstract and concrete. The person is, intellectually

speaking very advanced, but outside the academic realm, it doesn't work.

But no one can doubt Kripke's intelligence. Early in life, his

mathematical gifts were seen and he was way ahead of the others in

mathematics as a pupil in school. Then he went to Harvard and later became a

professor at Rockefeller University. He was later hired by Princeton

University. He is now retired, but still runs the lecture circuit. He is

always thinking and has just recently been visiting professor at Hebrew

University in Israel. He hopes to continue visiting Hebrew University in the

future.

Kripke does not care much about providing a justification for

doing philosophy. When I asked him why he investigates the philosophy of

language, he said he works on this topic simply because he finds it

interesting. Pure intellectual curiosity drives him: "The idea that

philosophy should be relevant to life is a modern idea. A lot of philosophy

does not have relevance to life. Ethics and political philosophy are

relevant to life. The intention of philosophy was never to be relevant to

life. But ethics and political philosophy can be relevant."

I ask him

whether it is a negative that philosophy now is connected to a professional

career and not the unconditional search for truth it once was. His reply:

"Perhaps it never was an unconditional search for truth. The great

philosophers did it as a professional career. The Medieval philosophers were

monks, but also professors. Descartes was not a professor, but he did a lot

of teaching."

I remark that

Michael Dummett claims that academics don't have any special duty to be

engaged in social questions, but because they can make their own schedules

they can use this privilege. Kripke replies, "I don't think there is

anything special academics can do."

We turn from talking about the

nature of philosophy to Kripke's religion and his relation to the Middle

East, where he has been working. Hebrew University, where he has been

studying, is one of the most well-known universities in the Middle East, and

located in Jerusalem.

Kripke is Jewish, and he takes this seriously:

"I don't have the prejudices many have today, I don't believe in a

naturalist world view. I don't base my thinking on prejudices or a world

view and do not believe in materialism." He claims that many people think

that they have a scientific world view and believe in materialism, but that

this is an ideology.

In spite of his religious views, he does not

think that the division of land in Israel-Palestine can be determined by

appealing to the Bible. "I don't believe in religious groups that want to

divide the country on the basis of fundamentalist principles. Politics and

religion should not be mixed."

I ask him whether he thinks that the

co-existence of different groups in an area is beneficial, and whether

Jugoslavia and the Middle East show us that mixing different cultures can be

dangerous: "There are cases where it is better to divide. I don't think it

always works in practice. The problems in Europe with foreign workers that

meet prejudices are that they are not integrated."

I ask him if there

is a lot of racism in the Middle East. His reply: "There is racism both

ways. Much of this is based on prejudices the Arabs believe in many things.

Before Jews were allowed to travel to Cairo, many Arabs thought that Jews

had horns. Prejudices are crucial for understanding racism."

Finally,

I ask him how philosophy can contribute to promoting peace in the Middle

East. His reply: "I don't think philosophy can contribute more than other

disciplines. Practical philosophy may contribute here, but not all

philosophers. That would have been nice, but in practice it is not

possible."

Kripke is a peculiar man with a sharp intellect. He talks

fast and he thinks perhaps even faster. He drinks a lot of tea and waves to

get the waiter's attention. He told me many stories about Wittgenstein. But

when it comes to practical issues, it is more difficult to make him talk.

Still, it is a great experience to have met him.

Saul Kripke to give IU lecture

Indiana University, September 21, 2007

Edited by Andy Ross

Saul Kripke, considered by some to be the world's greatest living

philosopher and logician, will deliver the inaugural Presidential Lecture at

Indiana University, IU President Michael McRobbie announced today.

Kripke, 66, is known for his contributions to modal logic and related

logics, his theory of truth and his interpretation of the work of the

philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. His best-known work is Naming and

Necessity, published in 1980 and based on lectures that he gave while at

Princeton University.

Kripke grew up in Omaha, Nebraska, where his

father was a rabbi and his mother wrote Jewish educational books for

children. He began writing philosophical essays while in high school. He

attended Harvard University, where he earned a degree in mathematics.

He has been a faculty member at Rockefeller, Cornell and Princeton

universities. Since 2002, he has taught at the Graduate Center of CUNY in

midtown Manhattan. This fall, the center established the Kripke Center to

promote the study of his philosophy.

In 2001, Kripke received the

Schock Prize for Logic and Philosophy, given by the Royal Swedish Academy of

Sciences and regarded as the Nobel Prize in those fields.

Kripke on Naming and Necessity

By Arif Ahmed

Times Literary Supplement, June 14, 2018

Edited by Andy Ross

Saul Kripke has contributed to two related problems concerning meaning and necessity.

The problem about meaning is simple. People make noises with their mouths and marks with their hands. What is the difference between those that are just noises and marks and those that manage to say things? How do words denote objects? Bertrand Russell said users of language somehow mentally associate the name "Napoleon" with a description that is true of that person and of nothing else.

Kripke considered the use of words to say how things might have been. It would be correct to say “Napoleon might have been victorious at Waterloo” but not to say: “The person whom Wellington defeated at Waterloo might have been victorious at Waterloo." Kripke says names are rigid designators that denote the same thing when we use them to describe any possible world. Descriptions are flexible. So names and descriptions are different.

Kripke suggests that what connects word to object is the transference of a name or of its etymological ancestors, from one speaker to another, in a communicative chain running back to the christening of the object that it names. What a name means is external to the minds of its users. A mature language is like a machine that one can use without knowing how it works. What stands at the far end of a chain depends on facts about its preservation across an extended community of speakers.

Kripke glossed Ludwig Wittgenstein to argue for a more radical conclusion. It is a familiar thought that to understand a word is to possess an internal standard for its use that can guide you, rightly or wrongly. But what fact about you could make this true?

Suppose we try to teach addition by explaining it to persons A and B. We give them examples, we teach them rules, we assume their minds contain the same relevant images and memories, and so on. Then we ask them to calculate a new sum. A gets it right but B gives a wrong answer. Yet B doesn't see the problem. He says he is doing everything right. What looks to us like a bizarre deviation from his training looks to B like the natural continuation of it.

Must there have been a difference between A and B, in terms of their training, their inner lives, or anything else that could justify this difference in their responses? Wittgenstein says no. There is nothing in anyone's mind that could be the kind of understanding of a word that guides its use. Kripke concludes that the idea of understanding is an illusion.

When we follow a rule, we do so blindly. Our training in the use of words brings it about that we all use words in similar or at least in mutually predictable ways, but not because we all grasp the same meaning. Nothing that you grasp could do what meaning is supposed to do. We simply have a brute tendency to do this and not that.

Kripke says it was essential to Nixon that he was born a man. That man might have been shorter and he might never have been president, but we can't imagine Nixon as having been born female. Kripke thinks it is obviously true that he might have been taller but might not have been a woman, or Chinese, or born of other parents. He has an intuition that this conveys an essential property of the man, not the name.

Kripke has transformed analytic philosophy with his contributions to these problems.

AR Kripke was a young demigod when as

a passionate graduate student of logic and philosophy

I experienced his

lectures in London and Oxford.

|

|

|