Niall Ferguson

By Janet Tassel

Harvard Magazine, May-June 2007

Edited by Andy Ross

"I believe the world needs an effective liberal empire and that the United

States is the best candidate for the job. All I mean is that whatever they

choose to call their position in the world — hegemony, primacy, predominance

or leadership — Americans should recognize the functional resemblance

between Anglophone power present and past and should try to do a better

rather than worse job of policing an unruly world than their British

predecessors."

Ferguson, Colossus: The Price of America's Empire (2004)

Niall Ferguson is Tisch professor of history and Ziegler professor of

business administration at Harvard University. At the age of 43, Ferguson

has produced eight books, and has another two in progress. And all while

commuting among Harvard, the Hoover Institution at Stanford (where he is a

senior fellow), and the United Kingdom, where his wife Susan, a media

executive, and their three children live. In 2002-3, for Britain’s Channel

4, he wrote and starred in a six-part history of the British empire. In

2004, he followed with American Colossus—both programs based on his books.

And in 2006, Britons watched his six-part The War of the World.

Graduating with first-class honors in 1985, he was a demy (a foundation

scholar) at Magdalen College until 1989. He then spent two years as a

Hanseatic Scholar in Hamburg and Berlin, where he learned German, worked on

his dissertation (subsequently his first book, Paper and Iron: Hamburg

Business and German Politics in the Era of Inflation, 1897-1927), and worked

as a journalist for British and German newspapers. In 2004, the year he

arrived at Harvard, Time magazine included him in its list of the 100 most

influential people in the world.

Ferguson is emphatic about the

benefits that accompanied British rule: "Without the spread of British rule

around the world, it is hard to believe that the structures of liberal

capitalism would have been so successfully established in so many different

economies around the world."

The War of the World takes the reader on

a long and gruesome march through the century-long racial tensions and

economic uncertainties that led to the Second World War and the descent of

the West into unimaginable horror.

"Had Britain stood aside — even

for a matter of weeks — continental Europe could therefore have been

transformed into something not wholly unlike the European Union we know

today — but without the massive contraction in British overseas power

entailed by the fighting of two world wars."

Ferguson, The Pity of War

(1999)

Ferguson must finish his book on Siegmund Warburg: "I was

gripped by the most important and certainly the most perplexing tragedy of

modern history, which was the tragedy of the Jews." Ferguson suggests that

the Scots are in many significant ways similar to the Jews.

Ferguson in front of a Soviet tank

By Andy Ross, December 31, 2006

The War of the World: History's Age of Hatred

By Niall

Ferguson

Allen Lane, 2006

Niall Ferguson is a glamorous figure, a relatively young Harvard professor

of history with a string of well regarded books to his credit and with roots

in Britain, first as a Glaswegian Scot and then as a brilliant young Oxford

don. His specialty, if you can call it that, is the history of the last

three centuries on both the global and European levels, with particular

focus on economic and financial history. His first book, based on his

doctoral thesis, was on the house of Rothschild and its massive influence

through its banking activities on wars in Europe in the nineteenth century.

His most famous book, The Pity of War, was about the 1914-1918 war and

speculated on how much better the history of the twentieth century might

have been if Britain had not declared war on Germany but instead let Germany

win, and perhaps establish a German empire stretching from the Atlantic to

the Pacific. His point was that the Germans could conceivably have stamped

out communism before it became a menace and as a result made the whole

fascist movement less murderous.

With that sort of background, a

reader naturally has high hopes for his new book on the Second World War and

its causes and consequences. The story fills the frame set by the twentieth

century, from September 11, 1901, to the rise of militant Islamism a hundred

years later. The motif for the title is the H.G. Wells novel, The War of the

Worlds, about a Martian invasion, which seems nicely to prefigure the

genocidal impact of the war machines that gave the century its unique brand

of horror. The central thread of the narrative is the argument that

multiethnic communities in Europe and elsewhere were driven both by racism

and by economic instability to commit murderous atrocities whose scale and

intensity were unprecedented in human history. There are three caveats to

the argument: (1) mixed communities without racist tension can survive

economic stress without bloodshed, (2) communities that see themselves as

racially mixed can prosper together if their economic circumstances are

stable, and (3) strong empires can contain multiethnicity and economic

turmoil, but weak or decaying regimes cannot. In short, the outcome is that

racism plus hard times equals trouble.

Ferguson's main claim with

regard to Nazi Germany is that economic turmoil generated by (1) the

hyperinflation in the Weimar Republic in 1923 and (2) the depression

following the Wall Street crash in 1929 in combination with (3) ongoing

communist agitation within the industrial workforce inspired by the

emergence of Soviet Russia was a sufficiently large triple whammy to make

Germans susceptible to racist provocation. As to the Germans' understanding

of their own racial identity, a rich tradition of artists like Goethe and

Wagner had romanticized it and philosophers like Nietzsche and Spengler had

thematized it, with the result that agitators like Hitler and Goebbels could

relatively easily grasp and subvert it. As usual in such scurrilous

undertakings, Jews were chosen as the prime scapegoats. Jewish prominence in

the world of finance and in the rise of the Bolsheviks was enough to make

them targets. As for the imperial context, both the Russian and the

Austro-Hungarian empires had gone and the new order in Europe was unstable.

Ferguson dwells long enough on all this to make it clear that Nazi

racism was absurdly irrational and unscientific, whether directed against

Jews or Slavs or any other aliens relative to the Aryan prototype. He also

points out in detail how similar racist sentiment accompanied the Japanese

drive into China from 1931 on. Happily, his history flies high above the

military details that every educated reader can be assumed to know ten times

over from previous histories, so all we have to read in this book are fresh

details about aspects of the whole sordid tale of the genocidal wars of the

mid-century that resonate with the concerns we still have as we confront the

challenge of surviving another century with the same old human atavisms just

below the skin. Happily, too, he continues the story through the more

murderous episodes of later decades, right up to the breakup of Yugoslavia

and the genocide in Rwanda, to establish that 1945 did not end the dynamic

his narrative demonstrates.

All of which seems well and good, in the

sense that a thesis that looks reasonable is sustained through a barrage of

historical facts that together should suffice to convince an unprejudiced

reader. The central claim that the natural racism of any human group can

become transformed when hard times destroy the economic environment within

which the group is accustomed to living, and tranformed moreover into

murderous insanity that available technology can amplify to genocidal

atrocity, is surely plausible. This is not special pleading for murderers.

But it is a warning. Humans cannot help but form groups with their own ideas

about who is in and who is out. We are always the best, and the dummies or

the lefties or the fascists or the unbelievers are always potentially at

risk. Any of us, if pushed hard enough, will push back. On this crowded

planet, where economic and other turmoil can spark conflict instantly and

where local conflicts can instantly become global, we do well to remember

that we can still be as dangerous as space aliens to each other. Ferguson

has done sterling service in marshalling our recent history to remind us of

this fundamental truth.

Some works by and about Niall Ferguson:

Washington Post, 2006

Boston Globe, 2006

Berkeley Globetrotter, 2006

The Guardian, 2006

Berkeley Globetrotter, 2003

National Post, 2001

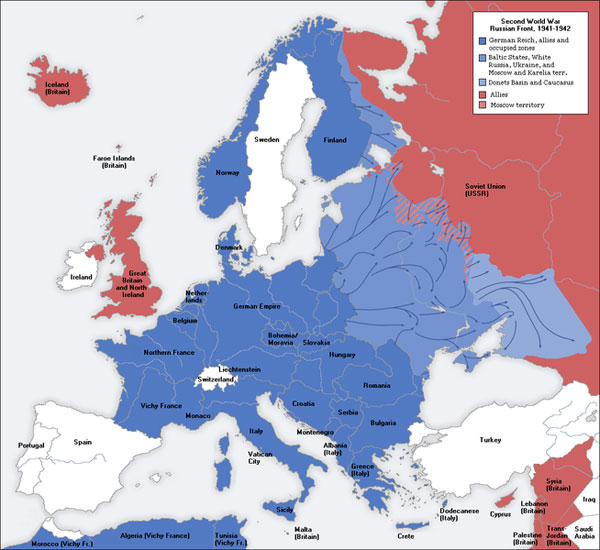

The greatest extent of the Nazi empire

By Niall Ferguson

Financial Times, September 13, 2008

Edited by Andy Ross

Hitler's Empire: Nazi Rule in Occupied Europe

By Mark

Mazower

Allen

Lane, 726 pages

Hitler

By Ian Kershaw

Allen Lane, 1030 pages

Hitler, The Germans and the Final Solution

By Ian

Kershaw

Yale

University Press, 394 pages

The Nazi empire turned out to be the least successful piece of colonisation

ever seen. Launched in 1938, the campaign to expand beyond Germany's 1871

borders peaked in late 1942, by which time the empire encompassed around

one-third of the European land-mass and 244 million people. Yet by October

1944 it was gone, making it one of the shortest-lived empires in all

history, as well as one of the worst. Why was the Nazi empire such a

horrible failure?

Mark Mazower grasps the fact that the Nazi regime

revealed its true character only in war and conquest. From the outset it was

intent on being an empire. The Nazis always intended to regard the

territories taken from the Soviet Union "from a colonial viewpoint", to be

"exploited economically with colonial methods". The difference that most

struck contemporaries was that, in eastern Europe, the colonised were the

same colour as the colonisers. Yet the Nazis had no difficulty with that,

thanks to the warped ingenuity of their own racial theories.

The

short duration of the Nazi empire was primarily for military reasons. Once

the Third Reich was embroiled in a war with not only the British Empire but

also the Soviet Union and the US, its empire was surely doomed. Yet

Mazower's book offers a secondary, endogenous explanation for the Third

Reich's failure as an empire.

In terms of simple demographics, there

was nothing implausible about putting 80 million Germans in charge of the

European continent. In theory, it should have been easier for Germany to

rule Ukraine than it was for Britain to rule Uttar Pradesh. For one thing,

Kiev was nearer to Berlin than Kanpur was to London. For another, the

Germans were genuinely welcomed as liberators in many parts of Ukraine in

1941.

Yet the Germans failed to exploit these advantages. What went

wrong? The answer can be given in four words: arrogance, callousness,

brutality and ineptitude. All empires are prone to these vices. But the Nazi

empire took them to such an extreme that any possibility of sustainable rule

was destroyed. Later empires worried about winning hearts and minds. The

Nazi empire was both heartless and mindless.

After

Operation

Barbarossa, Red Army prisoners were treated with such vicious indifference

that by February 1942 only 1.1 million were still alive of the 3.9 million

originally captured. Herded together in barbed wire stockades, they were

left to the ravages of malnutrition and disease. Nor were the Nazis content

to starve the conquered. They also relished inflicting violence on them,

ranging from impromptu beatings all the way to

industrialised genocide.

Added to arrogance, callousness and brutality was downright ineptitude.

The SS aspired to establish some kind of centralising grip on the empire.

But Mazower shows in detail how Himmler and his lackeys bungled the

resettlement of 800,000 ethnic Germans. Yet ultimate responsibility for the

dysfunctional character of the Nazi Empire lay with Hitler, whose preferred

method for pacifying occupied territory was "shooting everyone who looked in

any way suspicious".

Hitler was a specialist in destruction, whose

empire could not hope to endure. Sir Ian Kershaw's monumental biography of

Hitler is now republished in a single volume. Kershaw's early work focused

on popular attitudes towards the Third Reich. But as his biography evolved,

the centrality of Hitler became inescapable. As Kershsaw writes in Hitler,

The Germans and the Final Solution: "No Hitler: no SS-police state ... no

Hitler: no general European war by the late 1930s ... No Hitler: no attack

on the Soviet Union ... No Hitler: no Holocaust."

In many ways,

Hitler's empire was the reductio ad absurdum of a concept that by 1945 had

passed its historical sell-by date. In the course of the 20th century, it

gradually became apparent that an industrial economy could operate perfectly

well without colonies.

Germanisation of the east was an

impossibility. Easternisation of Germany was far more likely. By the end of

1944 around five million foreigners had been

conscripted to work in the

factories and mines of the old Reich. By a rich irony, the dream of a

racially pure imperium had turned Germany itself into a multi-ethnic slave

state.

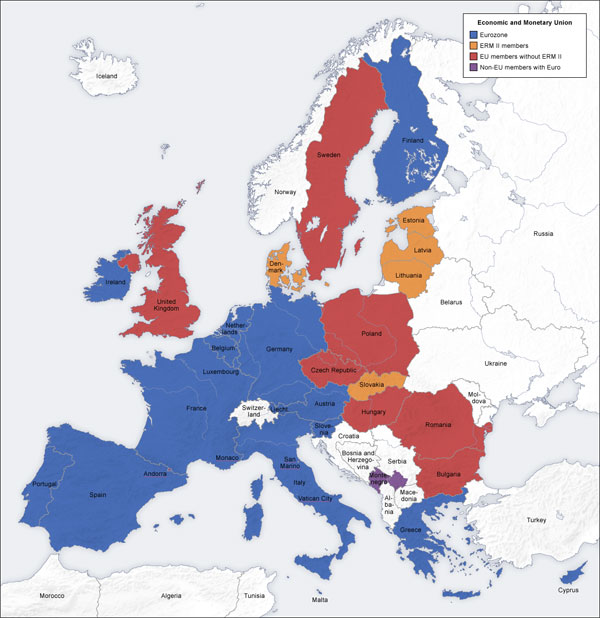

The European Union and Eurozone

AR Abysmal horror. Such humiliating incompetence from a people otherwise so practically talented suggests a hidden agenda. I see the Nazi drama as Wagnerian opera — a recrudescence of classical paganism punching a fist into the face of pious liberalism.